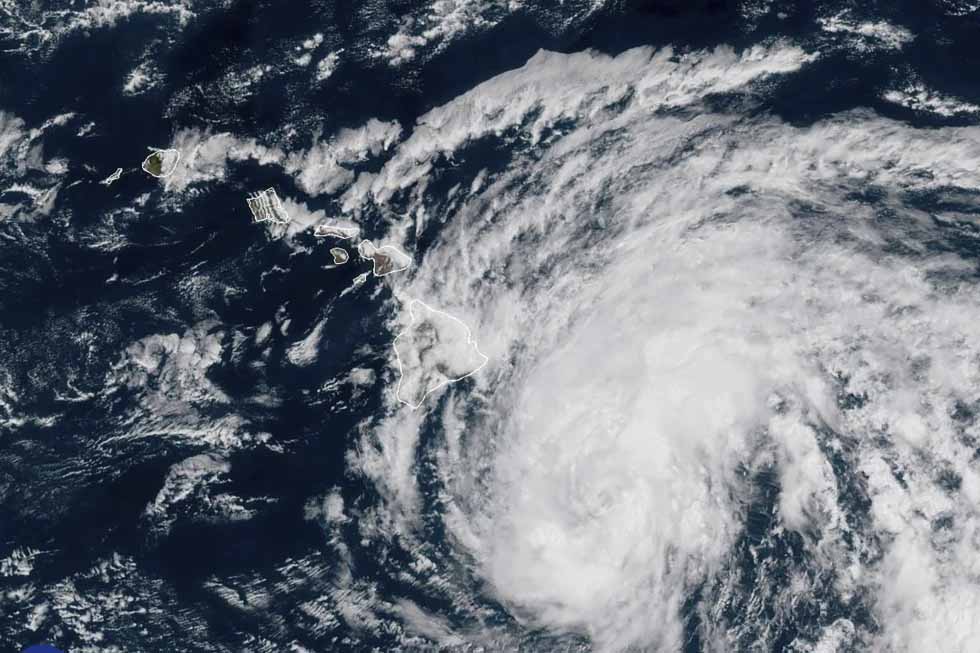

Hurricane Hone passed just south of Hawaii on Sunday, dumping enough rain for the National Weather Service to call off its red flag warnings that strong winds could lead to wildfires on the drier sides of islands in the archipelago.

Hone (pronounced hoe-NEH) had top winds of 85 mph (140 kph) Sunday morning as it moved westward, centered about 45 miles (72 kilometers) off the southernmost point of the Big Island, according to Jon Jelsema, a senior forecaster at the Central Pacific Hurricane Center in Honolulu. He said tropical storm force winds were blowing across the island’s southeast-facing slopes, carrying up to a foot (30 centimeters) or more of rain.

“As the rain gets pushed up the mountain terrain it wrings it out, kind of like wringing out a wet towel,” Jelsema said Sunday. “It’s been really soaking those areas, there’s been flooding of roads. Roads have been cut off by high flood waters there in the windward sections of the big island, and really that’s the only portion of the state that’s had much flooding concern at this point.”

Hurricane Gilma, meanwhile, increased to a Category 4 hurricane Saturday night, but it was still far east of Hawaii and forecast to weaken into a depression before it reaches the islands.

Some Big Island beach parks were closed due to dangerously high surf and officials opened shelters as a precaution, Big Island Mayor Mitch Roth said.

Hone, whose name is Hawaiian for “sweet and soft,” poked at memories still fresh of last year’s deadly blazes on Maui, which were fueled by hurricane-force winds. Red flag alerts are issued when warm temperatures, very low humidity and stronger winds combine to raise fire dangers. Most of the archipelago is already abnormally dry or in drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

“They gotta take this thing serious,” said Calvin Endo, a Waianae Coast neighborhood board member who lives in Makaha, a leeward Oahu neighborhood prone to wildfires.

The Aug. 8, 2023, blaze that torched the historic town of Lahaina was the deadliest U.S. wildfire in more than a century, with 102 dead. Dry, overgrown grasses and drought helped spread the fire.

For years, Endo has worried about dry brush on private property behind his home. He’s taken matters into his own hands by clearing the brush himself, but he’s concerned about nearby homes abutting overgrown vegetation.

“All you need is fire and wind and we’ll have another Lahaina,” Endo said Saturday. “I notice the wind started to kick up already.”

The cause of the Lahaina blaze is still under investigation, but it’s possible it was ignited by bare electrical wire and leaning power poles toppled by the strong winds. The state’s two power companies, Hawaiian Electric and the Kauai Island Utility Cooperative, were prepared to shut off power if necessary to reduce the chance that live, damaged power lines could start fires, but they later said the safety measures would not be necessary as Hone blew past the islands.

Roth said a small blaze that started Friday night in Waikoloa, on the dry side of the Big Island, was brought under control without injuries or damage.